“The Gift of a Human Part-“: Why Forensic Oversight Matters in Human Organ, Tissue or Cell Donation and Transplant

Introduction

Human beings are complex organisms composed of trillions of cells organized into tissues, and those tissues integrated into organs and organ systems that sustain life. Every heartbeat, breath, and thought depends on this remarkable biological architecture. When parts of this system fail through disease, injury, or inherited birth defect, modern medicine has developed the capacity to replace damaged cells, tissues, or organs with healthy counterparts from another human being. This life saving science of transplantation transforms a donation of cells, tissues, or organs from one person to another into a beacon of hope for patients whose own bodies can no longer sustain life functions. In line with WHO guiding principles and UN human rights frameworks, organ, tissue, and cell donation must remain voluntary, non-commercial, and ethically regulated, because no matter the cost involved in transplantation, no price can buy a human part—hence the enduring and deliberate use of the term “the Gift of a Human part,” reflecting dignity, altruism, and respect for human life.

Anatomical Gift vs. Organ ,Tissue or cell Donation & Transplant

The primary difference between an anatomical gift and organ, tissue, or cell donation lies in the purpose and disposition of the donation: organ/tissue/cell donation is for immediate transplantation to save or improve a life, while an anatomical gift (often meaning whole-body donation) is for medical education, research, or training. It is however possible for a person to engage in both anatomical gift (whole-body donation) and organ transplant donation, allowing them to potentially save lives through transplantation while also contributing to medical research and education.

This may be obtained from both living and deceased donors. This term is sometimes used In living donation, individuals may donate renewable or non-essential cells such as blood, plasma, platelets, bone marrow, peripheral blood stem cells, sperm, ova, etc., which are widely used in transfusion medicine, oncology, reproductive health, and immunotherapy.

Living donors may also contribute tissues including skin, bone, tendons, ligaments, hair, cartilage, amniotic membrane, and adipose tissue for use in burn care, orthopaedic reconstruction, trauma management, and regenerative medicine. In addition, certain organs can be safely donated by living persons under strict medical and ethical safeguards, most commonly one kidney, a portion of the liver, a lobe of the lung, part of the pancreas, or segments of the intestine.

Cadaveric or deceased donation greatly broadens the range of human parts as gifts, allowing for the recovery of vital organs such as the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, pancreas, intestines, uterus, and, in specialized contexts, vascularized composite allografts following confirmed death and appropriate consent. From deceased donors, numerous tissues and cells can also be procured, including corneas, sclera, skin, bone, heart valves, blood vessels, nerves, tympanic membranes, hematopoietic stem cells, pancreatic islet cells, and corneal endothelial cells, collectively demonstrating the profound life-saving and restorative potential of anatomical gifts. In deceased donation most legislations and ethical practice require that organs and tissues only be removed after death has occurred, which is colloquially known as the ‘dead donor rule’. Death is determined using clinical criteria that focus either on the circulation of blood in a person’s body, i.e. Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) or on the functions of a person’s brain- Donation after Neurological Determination of Death (DNDD).

Global Transplantation Landscape: Demand Far Exceeds Supply

Globally, the practice of donation and transplantation continues to grow, yet the gap between supply and demand remains dramatic. According to the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, more than 173,700 solid organ transplants were performed and 47,180 deceased donors recorded in 2024, with kidney and liver transplants constituting the largest volumes. However, these numbers meet only a fraction of global need, fulfilling less than 10% of actual demand for life-saving transplants. Living donors also contribute significantly, with nearly 41,000 living transplants reported across 90 countries. Despite these advances, hundreds of thousands of patients remain on waiting lists, often dying while awaiting suitable organs.

The Ethics, Organ Trafficking and Illicit Transplant Practices

The crux of the ethical dilemma lies in consent, dignity, and justice. Legitimate donation relies on informed, voluntary decision-making by donors or their families, guided by respect for human autonomy and the intrinsic worth of every body. International guiding principles assert that cells, tissues, and organs should be donated freely, without financial reward, and that payments or incentives that exploit vulnerable populations undermine altruistic donation and can fuel trafficking.

This enormous global shortfall has spurred tremendous scientific innovation and expanded public education about the value of donation. Yet it has also unveiled darker currents: illegal organ trade, trafficking, and unethical transplant practices that thrive where oversight is weak, transparency is absent, and regulatory systems lack robust forensic and ethical frameworks. The World Health Organization acknowledging both the promise of transplantation and the dangers posed by inadequate safeguards adopted Resolution WHA77.4 in 2024, urging Member States to strengthen regulatory frameworks, protect living donors from exploitation, integrate donation systems into national healthcare, and enhance ethical oversight of transplantation activities. This global commitment underscores the critical importance of governance, transparency, and accountability in ensuring that anatomical gifts are truly expressions of altruism and scientific excellence

Why Forensic Oversight Is Essential

In the absence of strong oversight, however, the line between life-saving practice and exploitative commerce can become alarmingly thin. With only a small fraction of global need met through ethical donation, desperate patients may turn to illegal avenues including transplant tourism and organ trafficking that exploit the most vulnerable. The WHO and other sources estimate that 5–10% of all organ transplants worldwide involve organs from illicit sources, with victims often drawn into trafficking networks through deception, coercion, or economic desperation. Reports suggest that over 100,000 illegal transplants may occur yearly, forming a criminal market valued in the hundreds of millions to over a billion dollars. These illicit practices not only violate human rights but also jeopardize public trust in legitimate donation systems and expose both donors and recipients to serious health risks, such as infections and poor surgical outcomes.

Forensic oversight plays a pivotal role in safeguarding transplant integrity. It involves rigorous documentation, chain-of-custody tracking of donated materials, post-mortem verification of donor criteria, and meticulous investigation of any suspicious or unexplained practices. These measures protect donors’ rights, uphold medical and legal standards, and ensure confidence in transplant programs. Transplant legislation and regulatory infrastructures( National Forensic Authority and National Transplant Agency) can deter criminal networks, support prosecutions of trafficking offenses, and provide clarity when disputes arise, thereby strengthening social trust. Moreover, registries and data systems mandated by forensic governance ensure that every donation is accounted for, monitored for safety and outcomes, and analyzed for trends that inform policy and practice. Without such oversight, gaps remain in the traceability and integrity of donated materials, leaving open the possibility of exploitation, fraud, and compromised health outcomes.

Conclusion: Protecting the Gift Through Science and Ethics

As global health authorities emphasize, ethical oversight, transparency, and harmonized regulation are not merely administrative concerns; they are healthcare imperatives that transform human whole body or parts as gifts from abstract medical concepts into trustworthy instruments of healing, education and research. Transplantation saves lives, alleviates suffering, and embodies human compassion—but only when anchored in ethical practice, scientific verification, and unwavering respect for the dignity of both donors and recipients. In this context, the cost of failing to invest in forensic oversight is measured not only in lost opportunities for healing, but in the erosion of trust that underpins all humane and equitable health systems.

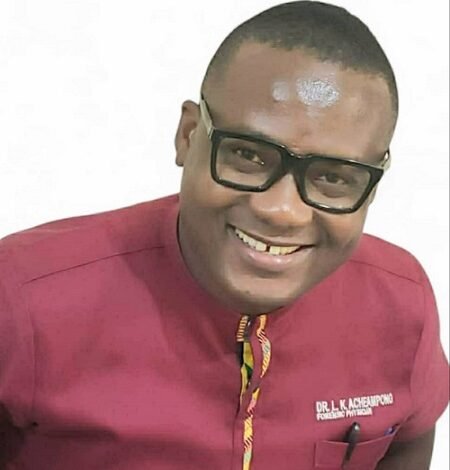

Written by: Dr. Lawrence Kofi Acheampong

Follow Ghanaian Times WhatsApp Channel today. https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VbAjG7g3gvWajUAEX12Q

🌍 Trusted News. Real Stories. Anytime, Anywhere.

✅ Join our WhatsApp Channel now! https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VbAjG7g3gvWajUAEX12Q