Book review: Ayeboafoh shares his life story

Title: Akyere – The Stream Which Never Dries Up

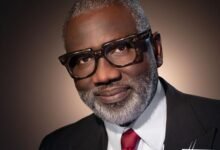

Author: Yaw Boadu–Ayeboafoh

Pages: 320

Printed: G-Pak Limited

Reviewer: Nanabanyin Dadson

There are a variety of motivations for people to write their biographies and share it with the world. The topmost four of these comprise to provide self-reflection; to identify legacy of achievements; to share experiences and knowledge, and to inspire others.

In “Akyere: The Stream Which Never Dries Up – My Life Story”, Yaw Boadu-Ayeboafoh, combines all four motivations into one huge narration in an autobiography whose setting traverses life in his village, schools, relationships and the corporate world from the 1960s through to the 2020s.

Ayeboafoh, being the very notable personality that he is in journalism, I will, for this review, attempt to navigate his 320 pages through a format that must be very familiar to his career. I am taking the liberty to look at “Akyere” through the popular basic journalism newswriting format – “Who did what, when, where, how and to what effect?”

Who is this man?

It may sound fictional but the story surrounding Ayeboafoh’s birth is real – he was almost not born. His parents had to wait seven long years after the loss of their first and second babies. Then finally when Ayeboafoh was born, his head could not sit steady on his neck, a physiological condition, the Akans refer to as “asram”. So for the best part of three years, the little boy had to be carried everywhere on her mother’s back and fed from her breasts.

To make the circumstances of Ayeboafoh’s birth even more curious to the reader is the fact that he was not born on Thursday; infact he was born on a Friday and therefore he should have been traditionally called Kofi. Why then? This is the first puzzle the reader discovers in “Akyere”.

To rise from the clichéd “humble beginnings” to the pride of place that Ayeboafoh occupies today is a tale of divine intervention, perseverance, commitment and sacrifice. From the very beginning, this boy from the village of Maase in the Afigya Kwabre North District of Ashanti had to take his education, both formal and informal, in both hands.

From walking long distances through forests and farms to begin school in 1963 at the age of five at Wenchi, through the days at Osei Kyeretwie Secondary School in Kumasi and years of sixth form at Asankragwa Secondary School, the lad seems to have set his sights on the path of learning. His life depended on it.

Thanks to the gift of academic brilliance that he demonstrated right from the beginning, Ayeboafoh, through many ordeals and challenges that may have discouraged many a young lad to throw up their arms and quit pursuing education, trod on.

Today, here he stands tall; not literally in terms of height, but tall among his peers for his academic knowledge, native wisdom, management skills, organisational politics and good human relations.

From my own reading and observation I would also add that Ayeboafoh is not a person who suffers injustice. Let someone carry injustice to his backyard and whoever it is will meet an indomitable spirit who will fight what he considers to be unjust to the daring point of staring straight down the barrel of a policeman’s rifle.

What is this all about?

Of course, “Akyere” is an autobiography and therefore the reader is not to expect anything outside what happens in the writer’s life. As stated by the character Jacques in Shakespeare’s As You Like It, “All the world is a stage; And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts.”One man plays many parts indeed but surely men like Ayeboafoh play many more roles than others.

There are so many events that catch the reader’s attention and many others that may resound in the reader’s own life. Here are a couple. He writes:

When I applied for admission to Boamang LA, I was nearly denied access because they found me too young for the class and did not know my level of knowledge. In my first term at Boamang which was the second term of the 1964/65 academic year, I placed first jointly with a girl, Akosua Addai, but the thinking at the time, probably the emergence of gender advocacy, was that if a boy tied with a girl at a position, it should be given to the girl. So for the only time during our Upper Primary, I placed second but took up that position until we got to middle school where there was only one stream and we had to merge.

Another passage: In the first term in Lower Six, the Scholarship Secretariat delayed the release of funds for students on government scholarship. All sixth form students were under scholarship. The school authorities asked us to go home and bring our school fees so that whenever it was released, what we had paid would be credited to our accounts. However, our seniors told us that when they paid, nothing was ever refunded to them.

Armed with this knowledge and knowing that my mother struggled to see me through OKESS, even as a day student, I decided to petition the Head of State, Gen. I.K. Acheampong, for redress.

One more: I left Legon and entered into the life of National Service. Before we completed school, I had a two-week interval for my last paper. Thus, I came home to Maase and that is when I met my first wife whom I had known as we all grew up. Within these two weeks, we became friends and before I returned to school, I knew she would be pregnant and indeed she was, the fruit being my first son, Kwame Nsiah Wiafe Akenten whom I named after my childhood friend.

The confidence of pregnancy Ayeboafoh demonstrates in this passage in “Akyere” reminds me of Okonkwo in Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart where Okonkwo, a man of few words, carried his first wife, Ekwefi, into his obi and in the darkness of the night he began feeling for the loose end of her wrapper. What confidence! One hit, one baby.

So as one reads through “Akyere”, one finds that the substance of what he recounts in his life journey are the everyday events that occur in life; nothing is fabricated or forced. Allow me to cite just one more passage that shows his soft side. His girlfriend, or someone he thought was his girlfriend, left him abruptly and guess what Yaw did: he fainted. Yes, fainted.

He writes: I do not know how I took it but that evening, I found myself on admission at the Tamale Hospital. I was later told in the office that as soon as the lady left, I shouted her name and collapsed and had to be carried down into a vehicle and transported to the hospital where I was admitted. I stayed overnight and was discharged the next evening.

In the course of the day, I was visited by Mr Bebaako-Mensah, the Deputy Regional Minister, Mr A.B.T. Zakaria, an elder brother of Mr Zakaria who served for a long time as the Registrar of the University for Development Studies, Mr Ibrahim Mahama, then Deputy Secretary of Agriculture, AlhajiJawula and others from the Regional Administration as well as the Hospital Administrator.

Yaw’s journey through his schooling, media, especially at Graphic Communications Group brought him into contact with various individuals who became prominent people in the society. These include former president John Dramani Mahama who was his roommate at Commonwealth Hall at Legon, Ministers, Members of Parliament, Traditional Rulers, Chief Executives and Diplomats.

Conversation Tone

How does the writer communicate all these events in his book? He does so in a very relaxed, almost informal manner. His tone is conversational and he reaches the reader as someone he is sharing “filla” with. This style is usually difficult to handle as there are many occasions on which the writer seems to be going back and forth and also sounding repetitive.

While he is on a particular stream of narration, he leaves the main issue and goes to another sub-story only to return to the main stream once more. This back-and-forth may appear somehow frustrating for those readers who expect a linear plot narration and have no time for sidekicks.

Again, Ayeboafoh writes in English alright but a careful reader can discern that sometimes he thinks in vernacular, in his Asante Twi language, before writing whatever he has to say in English. For example, he describes his outfit during his study in India: “I wore a brightly coloured Islamic type of dress, up and down, to school”.

In the style of telling his story, the writer sometimes comes rather too close to be kicking the hornet’s nest. He conveys his messages in a too frank and unabashed manner disregarding the feelings of others whose names are mentioned in the narration. He even does it to himself. Can anyone imagine that Ayeboafoh actually narrates how he wrote a school examination for another candidate?

Especially as he spent a cumulative 32 years at Graphic, much of his candid references occur in recalling events during the time he was there occupying various positions. Predictably some people mentioned by name may feel uncomfortable and would have wished that the writer let sleeping dogs lie.

“Akyere – The Stream Which Never Dries Up” is not just a work of literature; it is more than that. It presents itself as an inspiration to all people who have faced considerable changes that have threatened to smother their dreams. Ayeboaafo credits his successes to his Maker, Oboadee Nyame, but under that umbrella of Grace he shows how a strong to-do-spirit can contribute in no small measure towards achieving one’s personal goals.

The last word of this review goes to all parents to spare a little of their time to put into writing their life stories, not necessarily in book form so that their offspring will grow to know who their parents really were. These days when older generations hardly communicate with the GenZees, such an exercise may help to bridge the culture gap.

“

There are so many events that catch the reader’s attention and many others that may resound in the reader’s own life.

“